Humans spend about 35 minutes each day chewing. This equates to more than a full week per year. But that’s nothing compared to the time our cousins spend chewing: chimpanzees chew for 4.5 hours a day and orangutans 6.6 hours.

The differences between our chewing habits and those of our closest relatives offer insights into human evolution. A study published Wednesday in the journal Science Advances explores how much energy people use when chewing and how this may have guided – or guided by – our gradual transformation in modern humans.

Chewing, in addition to keeping us from choking, makes the energy and nutrients in food accessible to the digestive system. But the very act of chewing requires us to expend energy. Adaptations to teeth, jaws and muscles all play a role in the efficiency of human chewing.

Adam van Casteren, author of the new study and an associate researcher at the University of Manchester in England, said the scientists did not delve into the energy costs of chewing in part because compared to other things we do, such as walking or running, it is a thin slice of the energy-efficient pie. But even relatively small gains can play an important role in evolution, and he wanted to find out if this could be the case with chewing.

To measure the energy that goes into chewing, van Casteren and his colleagues equipped the study participants with plastic hoods that look like “an astronaut’s helmet,” he said. The hoods were connected to tubes to measure oxygen and carbon dioxide from breathing. Since metabolic processes are fueled by oxygen and produce carbon dioxide, gas exchange can be a useful measure of how much energy something takes. The researchers then gave the subjects a gum.

However, the participants did not receive the sugary type; the gum bases they chewed were tasteless and odorless. Digestive systems respond to flavors and scents, so the researchers wanted to make sure they were only measuring the energy associated with chewing and not the energy of a stomach preparing for a tasty meal.

Test subjects chewed two gums, one hard and one soft, for 15 minutes each. The results surprised the researchers. The softer gum increased the participants’ metabolic rates by about 10% more than when they were at rest; the harder rubber caused a 15% increase.

“I thought there wouldn’t be a big difference,” van Casteren said. “Very small changes in the material properties of the object you are chewing can cause quite substantial increases in energy expenditure and this opens up a whole universe of questions.”

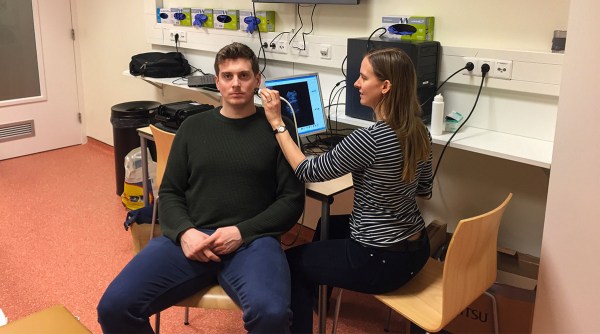

An undated photo provided by Amanda Henry shows a researcher measuring his subject’s chewing muscles with an ultrasound wand. Spending less time on chewing can go hand in hand with human evolution. (Image credit: Amanda Henry via The New York Times)

An undated photo provided by Amanda Henry shows a researcher measuring his subject’s chewing muscles with an ultrasound wand. Spending less time on chewing can go hand in hand with human evolution. (Image credit: Amanda Henry via The New York Times)

Since chewing harder foods, or in this case harder gum, requires a lot more energy, these findings suggest that the metabolic costs of chewing may have played an important role in our evolution. Making food easier to process through cooking, mashing food with tools, and growing crops optimized for consumption may have eased the evolutionary pressure for us to be super chewers. Our evolving chewing needs may even have shaped the look of our faces.

“One thing we haven’t really been able to figure out is why the human skull looks so funny,” said Justin Ledogar, a biological anthropologist at East Tennessee State University who was not involved in the study. Compared to our closest relatives, our facial skeletons are delicately built with jaws, teeth, and chewing muscles that are all relatively small. “All of this reflects a reduced dependence on forced chewing,” he said.

But he added that our flatter faces and shorter jaws allow us to bite more efficiently. “It just makes the whole feeding process metabolically less expensive,” Ledogar said. Humans have developed ways to chew smarter, not harder. Van Casteren, who hopes to continue his research using real foods, said he is excited about the prospect of learning more about the evolution of humans.

“Knowing the environmental, social and dietary causes that brought us here is infinitely interesting to me,” he said, because it allows humanity to “try to work out the foggy road that awaits us.”

This article originally appeared in the New York Times.